From cotton sleeves to cotton sleeves in three generations, a Chinese proverb says. So do other proverbs, in just about every language, state that MOst family fortunes are made and squandered in three generations.

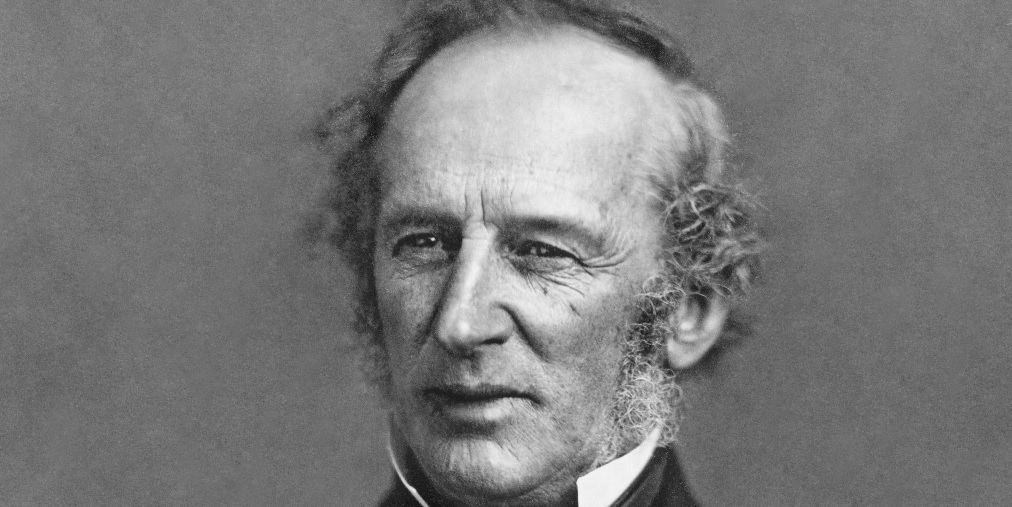

- Cornelius Vanderbilt was one of the greatest industrialists of the late 19th century, amassing an enormous fortune.

- But 50 years later, all the money was gone.

- The Vanderbilts made some key investing mistakes that led to their ruin.

Cornelius Vanderbilt might have been the greatest capitalist in history.

When he was just 16, in 1810, Cornelius borrowed US$100 from his mother. Using that money, he went on to build a fortune of around US$100 million. That would be worth over US$200 billion today. And it was roughly equivalent to 50 percent of the holdings of the U.S. Treasury at the time.

This kind of wealth was unheard of back then. It made Vanderbilt one of America’s richest men.

But within just 50 years of Cornelius’s death, the Vanderbilt family fortune was completely gone.

Even if you’re not wealthy beyond imagination, like the Vanderbilts were, there’s a lot to learn from their story of boom and bust. And you can do – today – the one simple thing that the Vanderbilts didn’t to ensure that your wealth doesn’t vanish within a generation.

The road to losing a family fortune

Cornelius started his shipping business by buying a passenger boat, which he then built up into a small passenger fleet. Eventually, he moved into the steamboat business. And having made a small fortune in shipping by his 50s, he turned his attention to building a railroad empire, which was his focus until his death.

Cornelius had a natural talent for business – handling the money, the competition, the costs and revenues, the deals and the relationships with everyone from the top to bottom of the food chain. He was a fervent believer in the merits of free competition, laissez faire (that is, letting things take their own course without interfering) and that government should play a minimal role in commerce. The entire Vanderbilt corporate life was built and operated under these beliefs.

For example, when he got into shipping, the industry was dominated by companies that had been granted monopoly rights on certain routes. Cornelius took them on with ferocious competition – cutting costs, reducing fares to almost zero and building and deploying faster ships. Almost without fail he prevailed, driving numerous incumbents either out of business, or into his arms. His opponents simply could not keep up. He brought this same mind-set into railways.

After his death in 1877, Cornelius’ son William took over the portfolio. Rather incredibly, William doubled the value of the Vanderbilt fortune to US$200 million by the time he died in 1885.

Then the rot set in…

William’s family inherited the Vanderbilt fortune and proceeded to squander it. They lived a lifestyle that their grandfather would never have contemplated. They built grand houses in locations frequented by the rich and famous… including ten palatial houses in Manhattan. These were all playthings, vanity projects to satisfy egos.

Within 30 years of Cornelius’ death, no member of the Vanderbilt family was among the richest in the U.S. And within 50 years of his death, the fortune was completely gone.

When I look at this story, I have to conclude that while Cornelius might have been the greatest capitalist on the planet, he was not a great investor.

Yes, we can lay the blame for the demise of the family fortune on later generations. But Cornelius essentially laid the foundations for this decline with his own hand.

Where Cornelius went wrong

First, practically all of his wealth was tied up in railroad and shipping stocks. He did not diversify across other industries, or across companies. It worked for him personally because he was intimately involved in running and managing these companies. But later, these companies were run and controlled by someone else. Having all of your wealth in one or two industries can destroy your portfolio if disaster strikes.

And having an entire fortune tied up in shares that can be sold at the drop of a hat made it all too easy for his heirs to say “I want to build this grand house for myself — let’s sell some shares today”. I think this was a key part of the demise of the Vanderbilt fortune. Having your entire wealth tied up in shares allows undisciplined owners to react to whims and short-term pressure. Having a mix of assets, that perhaps cannot be sold on the back of a phone call to a broker can guard against short-term temptations and whims. We’ve always stressed the importance of diversification and have written about how to make sure your eggs aren’t all in one basket, here.

The second major fault in the Vanderbilt portfolio was that it held very little in the way of hard assets. It did not include much land or real estate. And he owned zero investment properties, mines, or large farmlands.

Yes, Cornelius built a nice house for himself, and had some offices and some commercial space for his businesses. But he never invested in the most spectacular urban growth story of the century. He was running businesses in the financial heart of the country, a city that was growing by leaps and bounds… but he never bought land in New York City for development into commercial buildings. He loved dividends but didn’t see the cash flows that would come from investing in New York’s burgeoning real estate market.

Just think of what the family fortune might have looked like if Cornelius had parked, say, 20 percent of his shipping and railway generated earnings over the years into land and buildings in what has become a pre-eminent global financial center. This is something that we firmly believe everyone should do.

And an added bonus of real estate would have meant less liquidity. It’s easy to sell traded shares on a whim, but it’s a lot more difficult to dispose of an office tower. Lower liquidity might have prevented such a rapid demise of the Vanderbilt fortune, simply because it would have been more time-consuming and difficult to sell assets.

How things could have gone

Vanderbilt wasn’t the only family dynasty spawned in the 19th century. Two other families built up massive fortunes during this time. And both of those dynasties are still thriving 150 years later. These are the Jardine family (which co-founded the Hong Kong-based conglomerate Jardine Matheson, and the Swire family, which founded the London-headquartered Swire Group conglomerate.

Both of these family companies started out in concentrated businesses – but diversified into a range of different businesses. Jardine started out selling opium, cotton, tea and silk. Today, the company is involved in motor vehicles, property investment and development, food retailing, home furnishings and luxury hotels, just to name a few sectors. There are more.

Meanwhile, Swire started out in the textile trade. Today, it’s involved in property, aviation, beverages and food, marine services and trading and industrial industries.

Real estate also became a vital core business of both companies. Both invested in Hong Kong back when it was a proverbial backwater. Today, it’s the Asian equivalent of New York.

These families did the two things that the Vanderbilts did not. And today, many generations later, both of these families are still worth billions of dollars.

What we can learn from the Vanderbilts

The two things to take away from this story are that diversification and a core of “hard assets” should be guiding principles for all of us – even if we will never come close to mimicking Vanderbilt’s wealth. With a well-diversified portfolio that includes hard assets like real estate, you can survive just about any crisis… and grow your wealth for years to come.

Good investing.